Putin's Russia is a country that ruthlessly suppresses dissent.

When charismatic opposition leader Boris Nemtsov was shot dead on a Kremlin bridge in February 2015, more than 50,000 Muscovites expressed their shock and outrage the next day at the brazen murder. Police stood by while they rallied and chanted anti-government slogans.

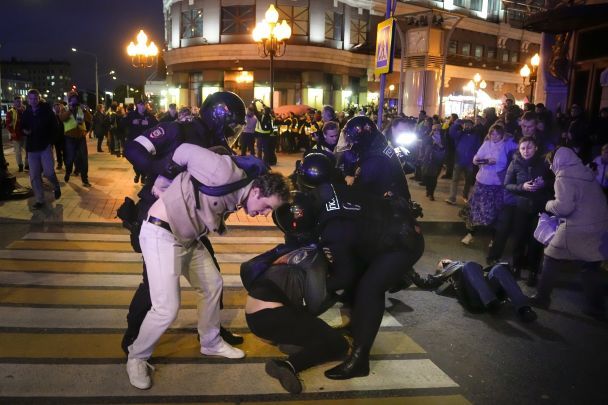

Nine years later, stunned and enraged Russians took to the streets on the night of February 16 when they heard that popular opposition politician Alexei Navalny had died in prison. But this time, those laying flowers at makeshift memorials in big cities were met by riot police, who arrested and dragged hundreds of them away.

Associated Press writes about this.

Over the years, Vladimir Putin’s Russia has completely transformed into a country that ruthlessly suppresses dissent. Arrests, trials and long prison sentences have become commonplace, especially after Moscow's invasion of Ukraine.

Along with its political opponents, the Kremlin also targets human rights groups, independent media and other members of civil society organizations, LGBTQ+ activists and representatives of certain religious denominations.

“Russia is no longer an authoritarian state – it is a totalitarian state,” said Oleg Orlov, co-chair of Memorial, a Russian human rights group that tracks political prisoners. “All these repressions are aimed at suppressing any independent statements about the political system of Russia, the actions of the authorities or any independent public activists.”

A month after he made those comments to the Associated Press, Orlov, 70, became his group's own statistic: He was handcuffed and led from a courtroom after being found guilty of criticizing the military in Ukraine and sentenced to 2.5 years imprisonment.

Memorial estimates that there are about 680 political prisoners in Russia. Another group, OVD-Info, reported in November that 1,141 people were behind bars on politically motivated charges, more than 400 had received other sentences and about 300 more were under investigation.

The USSR disappears, but repression returns

Orlov says there was a time after the collapse of the Soviet Union when it seemed that Russia had turned the page and large-scale repression was a thing of the past.

Although there were isolated cases in the 1990s under President Boris Yeltsin, Orlov says large-scale crackdowns began slowly after Putin came to power in 2000.

Exiled oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who spent 10 years in prison after defying Putin, told the AP in a recent interview that the Kremlin began cracking down on dissent even before his arrest in 2003. He purged the independent television channel NTV and began persecuting other recalcitrant oligarchs such as Vladimir Gusinsky and Boris Berezovsky.

Asked if he thought then that repression would reach today's scale – hundreds of political prisoners and prosecutions, Khodorkovsky said: “I rather thought that he (Putin) would snap earlier.”

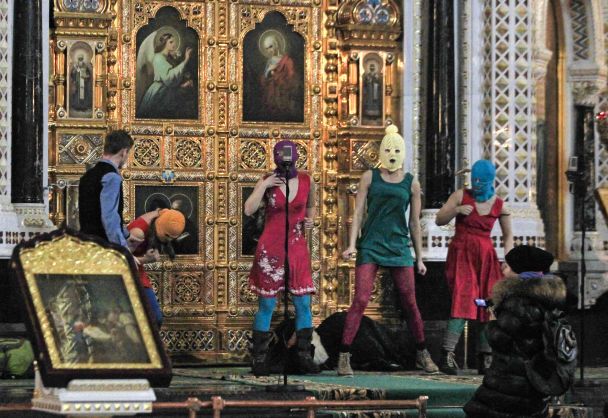

When Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and her colleagues from Pussy Riot were arrested in 2012 for singing an anti-Putin song in Moscow's main Orthodox cathedral, their two-year prison sentence came as a shock to her, she recalled in an interview .

“At the time it seemed incredible (a long prison sentence). I couldn’t even imagine that I would ever be released,” she said.

Growing intolerance towards dissent

When Putin returned to the presidency in 2012, having escaped the four-year term limit of prime minister, he was met with mass protests. He considered them inspired by the West and wanted to nip it in the bud, says Tatyana Stanova of the Carnegie Russia-Eurasia Center.

Many were arrested, and more than a dozen received up to four years in prison after these protests. But for the most part, according to Stanova, the authorities “created conditions in which the opposition could not flourish,” rather than dismantling it.

This was followed by a flurry of laws that strengthened the regulation of protests, providing authorities have broad powers to block websites and monitor users online. Groups were labeled with the restrictive “foreign agent” label to weed out what the Kremlin saw as harmful outside influences fueling dissent.

Navalny was twice convicted of theft and fraud in 2013-14, but received suspended sentences. His brother was arrested in what was seen as a move to put pressure on the opposition leader.

Moscow's annexation of Crimea in Ukraine in 2014 sparked a surge of patriotism and boosted Putin's popularity, emboldening the Kremlin. Authorities have restricted the activities of foreign-funded non-governmental organizations and human rights groups, declaring some of them “undesirable”, and have harassed critics online, fining them and sometimes arresting them.

Meanwhile, tolerance for protests became thinner. Demonstrations led by Navalny in 2016–17 led to hundreds of arrests; mass rallies in the summer of 2019 led to several more demonstrators being convicted and imprisoned.

In 2020, the Kremlin used the COVID-19 pandemic as a reason to ban protests. Until now, authorities often refuse permission to hold rallies, citing “coronavirus restrictions.”

Following Navalny's poisoning, recovery in Germany and arrest upon his return to Russia in 2021, repression intensified. His entire political infrastructure was outlawed as extremist, and his allies and supporters were threatened with persecution.

The opposition group Open Russia, which Khodorkovsky supported from abroad, was also forced to cease its activities, and its leader Andrei Pivovarov was arrested.

Orlov's Memorial group was shut down by the Supreme Court in 2021, a year before it won the Nobel Peace Prize as a symbol of hope for post-Soviet Russia. He mentioned his lack of confidence in the court's decision.

“We couldn’t imagine everything the next stages of the spiral are that there will be a war and all these laws will be passed to discredit the army,” he said.

War and new repressive laws

After the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia passed new repressive laws that suppressed any anti-war protests and criticism of the military. The number of arrests, criminal cases and trials has grown by leaps and bounds.

The accusations ranged from donating money to human rights groups helping Ukraine to being a member of Navalny's extremist group.

Kremlin critics went to jail, and their record didn't seem to matter. Navalny received 19 years, while another enemy of the opposition, Vladimir Kara-Murza, received the harshest sentence – 25 years for high treason.

Among those who were also convicted was a St. Petersburg artist who received seven years for replacing price tags in supermarkets with anti-war slogans; two Moscow poets received five and seven years for publicly reading anti-war poetry; A 72-year-old woman received 5 and a half years for two social media posts against the war.

< p dir="ltr">Activists say prison sentences are longer than before the war. Authorities are increasingly challenging sentences resulting in reduced sentences. In Orlov's case, prosecutors demanded a review of his previous sentence, which initially included a fine and was subsequently sentenced to prison.

Another trend is an increase in the number of trials in absentia, said Damir Gainutdinov, head of the human rights group Net Freedoms. She counted 243 criminal cases on charges of disseminating false information about the military, and 88 of them were brought against people outside of Russia – of which 20 were convicted in absentia.

Independent news sites were largely blocked. Many of them moved their editorial offices abroad, such as the independent TV channel Dozhd or Novaya Gazeta, and their work became available to Russians via VPN.

At the same time, the Kremlin expanded a decade-long crackdown on Russia's LGBTQ+ community in what officials called a fight for the “traditional values” professed by the Russian Orthodox Church before face of the “degrading” influence of the West. Last year, the LGBTQ+ “movement” was declared extremist and gender reassignment was banned.

The pressure on religious groups continues: hundreds of Jehovah's Witnesses have been persecuted throughout Russia since 2017, when the denomination was declared extremist.

The system of oppression is designed to “keep people in fear,” said Nikolai Petrov, a visiting researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

This doesn't always work. Last week, thousands of people, despite dozens of special forces, attended Navalny's funeral in southeast Moscow, chanting “No to war!” and “Russia without Putin!” — slogans that usually lead to arrests.

Uncharacteristically, the police did not intervene this time.

Recall, we previously wrote about Putin’s “purges” and death “under suspicious circumstances.” For more details, see the material “Exceeding Stalin: who and how the Putin regime is killing.”

Read the leading news of the day:

Related topics:

More news