Once the creators of these vehicles promised to revolutionize our understanding of transport.

The most advanced and fashionable form of transport today is Elon Musk's Hyperloop: a train rushing at high speed through a pipe from which air was pumped out. Rather, a train that will one day rush along such a pipe. May be. It is possible that Hyperloop will suffer the same fate as its predecessors in the matter of economical and convenient transportation of passengers and goods over long distances. Once the creators of these vehicles promised to make a revolution in the field of transportation, but in the end, their brainchildren either only made it to the stage of a demonstration model, or to full-size test tracks. Around the World recalls six such projects.

For the first time, the idea of transporting goods not just by road, but along guides appeared in Ancient Greece: as early as the 6th century BC, ships were dragged across the Isthmus of Corinth – along grooves greased with grease. Similar solutions were applied later, but the first railways, in our usual sense, appeared many centuries later – in Great Britain at the beginning of the 19th century, shortly after the invention of steam engines.

Rail transport has a number of advantages: less dependence on weather conditions than, say, conventional roads, the ability of trains to reach higher speeds compared to road transport while maintaining stability, higher carrying capacity, and so on.

Soon after the birth of the first railways, ideas for their improvement appeared: increasing the speed of movement (by reducing friction between the wheels and by using more efficient engines and reducing air resistance, which slows down the locomotive and wagons) and an increase in the volume of transported goods (due to an increase in carrying capacity and the length of the trains). All of the projects presented below were designed to solve either one of these problems, or both at the same time.

Beach Pneumatic Underground Road

(Beach Pneumatic Underground Railway)

An environmentally friendly and technologically advanced alternative to horse-drawn traction and burning coal in a furnace in the middle of the 19th century for driving cars on rails could become, as the inventors assumed, compressed air (they did not think much about ecology at that time): in a sealed pipe, they believed, it is necessary to create a vacuum or, conversely, an air pressure, which will move the composition. Such a transport system would have to resemble a greatly enlarged pneumatic mail channel – by that time this invention of the steam age was successfully operating in London (since 1853), as well as in Paris, Vienna, Berlin (since the 70s of the XIX century).

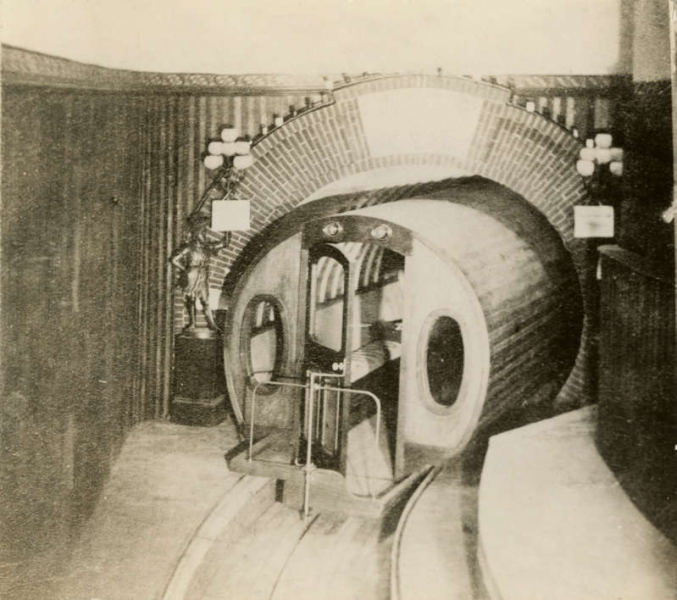

A few years after the opening of the world's first metro in London, New York, then already one of the most densely populated cities, also began to think about creating a convenient urban public transport. And then Alfred Eli Beach, an inventor, scientist and at the same time the publisher of the Scientific American magazine that still exists today, presented his project. Beach suggested digging tunnels under the streets of the city and moving carriages with passengers along them under the influence of the air flow created by huge compressors. To show that such a project was feasible, the inventor built a small demonstration model, and then, pretending to lay pneumatic lines under Broadway, built in 1870 a full-size experimental track section approximately 100 meters long. One car with a capacity of 22 passengers was running along the road – it was pushed in one direction by the incoming air stream, and in order to move the car in the opposite direction, the compressor worked to suck air out of the tunnel – like a vacuum cleaner.

The success of Beach's pneumatic transport system was colossal: in the first two years, the car carried more than 400,000 passengers. However, the price of the project turned out to be astronomical: the construction of a 95-meter tunnel with a diameter of 2.4 meters, a carriage, a richly decorated small station and an air injection and discharge system cost no less than $ 350,000 (for comparison: a worker in those years received about $ 90 cents a day, a dozen eggs cost 20 cents, and a pneumatic train ticket cost 25 cents). It seemed that the Beach Road had a great future, but in 1873 a financial crisis erupted, which put an end to the expensive and difficult project. The tunnel and the station were eventually dismantled, and the carriage was scrapped.

Balloon train of Yarmolchuk

In 1924, a young (26 years old) worker of the Kursk railway, Nikolai Yarmolchuk, invented the newest means of high-speed passenger transportation – an electric ball train. According to the inventor's idea, the train was supposed to consist of streamlined cylindrical carriages, resting in front and behind on two huge, human-sized wheels, each of which was a ball, from which the sides were sawed off. Electric motors were supposed to be placed inside the wheels. The train was supposed to ride along a chute, tilting around corners, and then returning to an upright position, like a vanka-vstanka, at a speed of up to 300 km / h. True, in order to draw up a project close to the real one, Yarmolchuk had to study first at the Moscow Higher Technical School (today the Bauman Moscow State Technical University), and then at the Moscow Power Engineering Institute. Finally, in 1931, the project was drawn up and presented to the Soviet government, and soon work began on the creation of cars (at first, models with a diameter of less than a meter) and a three-kilometer ring in the area of the Severyanin station of the Yaroslavl railway. Moreover, in August 1933, the Council of People's Commissars adopted a resolution: “On the construction of an experimental railway according to the system of N.G. Yarmolchuk. in the direction of Moscow – Noginsk “.

In the meantime, the first models of the ball train were tested, and successfully – they accelerated them to 70 km / h, the tests took place without crashes. But by the end of 1934, all work was canceled, and the project was forgotten: the difficulties that accompanied its implementation (construction and operation of the track, full-size cars, the state of the scientific and technical base as a whole), as well as the cost, turned out to be unacceptable. You can learn about the project today from numerous newspaper articles (not only in the Russian-language press, but also in the foreign one), newsreel footage showing the tests of the model, as well as from the exposition of the Central Museum of Railway Transport in St. Petersburg.

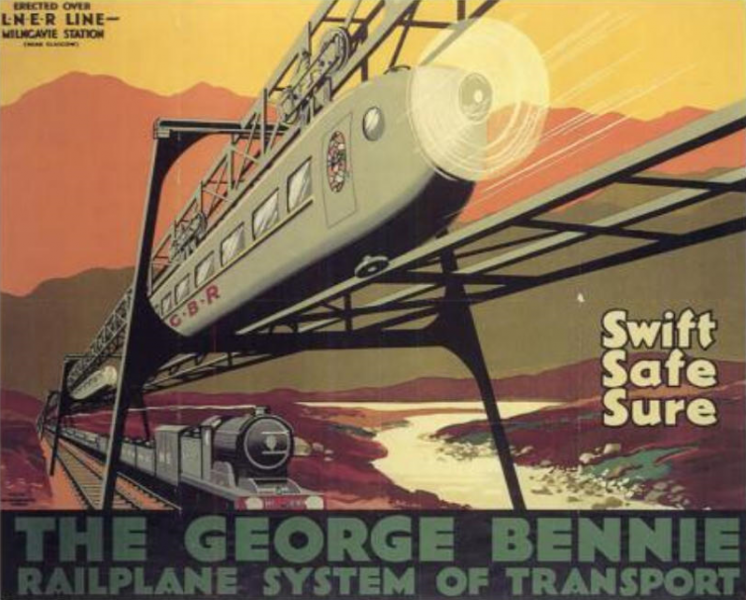

Benny's rail plane

(Bennie Railplane)

The idea of creating suspended railways appeared in the 1820s in England, but the first major project of a transport system of this kind was first implemented (not in the form of a demonstration line or attraction) in the German city of Wuppertal in 1901. Moreover, the Wuppertal Suspended Electrified Railway is still in operation, carrying up to 40 thousand passengers a day.

In the 1920s, Scottish inventor George Benny presented a design for a high-speed road to transport tens of thousands of passengers between major cities at speeds of up to 200 and even 250 km / h. The transport was a rail-borne aircraft – a hybrid of an overhead monorail and a train. Unlike a simple monorail, it had two rails – above and below – and it had to move over ordinary railway lines along the farm, carrying passengers, while trains on steam locomotive traction had to get the goods. The most interesting thing: the bullet-shaped comfortable metal cars had to be driven by propellers like aviation ones – hence the speed.

By 1930, in the Glasgow area, a full-size test section of the track with a length of 130 meters was built, the first cabins were assembled and tests began, both with cargo and passengers on board. The project was very much liked by both the public and potential investors, but no one was in a hurry to invest in it, with the exception of Benny himself: all work on the development and implementation of the project was paid from the inventor's own pocket. It was, on the one hand, in the high cost of the project, and on the other, in the financial crisis that broke out in the 1930s. Soon, towards the end of the decade, Benny ran out of money, and then World War II arrived. At its end, the track of the rail airplane was dismantled for scrap metal, and the carriage may be alive and lying somewhere to this day.

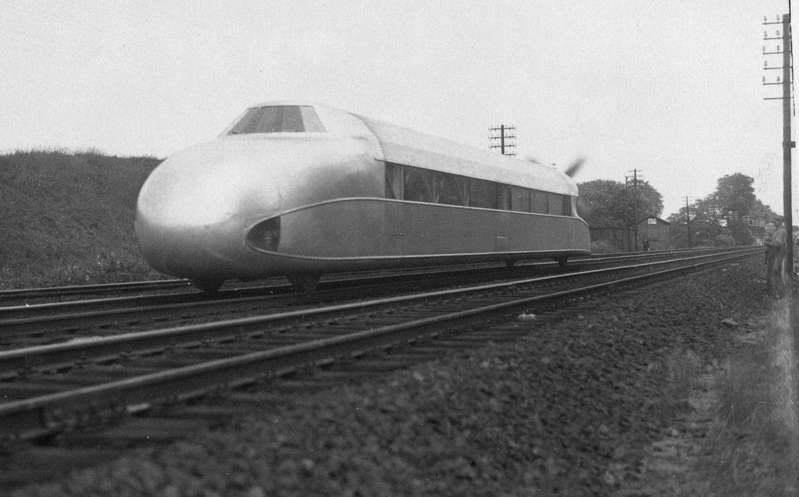

For the sake of fairness, we note that at about the same time in different European countries, projects of trains driven by propellers were created: these are Schienenzeppelin (pictured above) – rail zeppelin by German Franz Krukenberg (in 1931 on a public railway line, it accelerated to 230 km / h), and Abakovsky's air car, built in the USSR in 1921 and crashed on the second flight in its history (due to the poor state of the Tula-Moscow route). True, both of them, although they were driven by aircraft engines, were intended for ordinary railways. After World War II, they returned to the idea of air trains, but on a different level.

Aerotran

(Aérotrain)

The Aerotran hover train, invented in the mid-1960s by the French engineer Jean Bertin, was relieved of the need to overcome friction and accelerated due to a powerful engine and streamlined design: the Aerotran car was driven by an aviation (and, by the way, very noisy) motor, the train was moving along a T-shaped track laid on supports with a height of five meters (that is, in fact, “Aerotran” was a monorail) on an air cushion. Variants of cars with a linear electric motor were also developed.

The first demonstration model of “Aerotran” (on a scale of 1: 12) was presented in 1963, and already in February 1966, the first experimental track 6.5 km long was built, and the prototype car reached a speed of 200 km / h on it. New overpass tracks were built, new prototype cars, in parallel, work on Aerotran under license began in the United States, where cars and tracks were also built.

The French railway operator SNCF is seriously interested in the project. It seemed that Aerotran had a bright future. In addition, by 1969, the first passenger cars were built: the Aérotrain I80-250 car (pictured above) reached 25.6 meters in length, 3.2 meters in width and 3.3 meters in height, could carry up to 80 passengers and moved under the action of an air stream created by a propeller with a diameter of 2.3 meters. Tests showed that she could accelerate to 300 km / h. Work continued, prototypes moved faster and faster (up to 430 km / h – a record for hovercraft). And finally, on June 21, 1974, a contract was signed between the French government and Bertin's firm, according to which a commercial Aerotran line would be built from the La Defense quarter, which was actively under construction at that time, to Paris. Just 25 days later, the contract was terminated, and the following year it was announced that a high-speed TGV train would be launched between Paris and Lyon (another potential destination for Aerotran). In America, the tests were curtailed due to lack of money. At the end of December 1975, Jean Bertin died, and his project died with him. Today Aerotran cars can be seen in museums in France and the United States, flyovers and tracks still stand here and there as monuments to the project and its creators (in particular, an overpass near the village of Gomé-le-Châtel, 25 km north of Paris turned into a footpath).

The project was ruined by several factors: the need to build special tracks (while a competitor TGV could be used on railway lines), high noise levels (more than 90 decibels at a distance of 60 meters – this is about the volume of a jackhammer if you stand next to it) and “gluttony »Engines, which turned out to be unacceptable after the oil crisis of the first half of the 1970s. In 2013, French indie band Exsonvaldes released a video for the song “Aérotrain” , which used newsreel footage of a train test.

Repeat Video SETTINGS OFF HD HQ SD LO Skip Ads

Broad gauge railway

(Breitspurbahn)

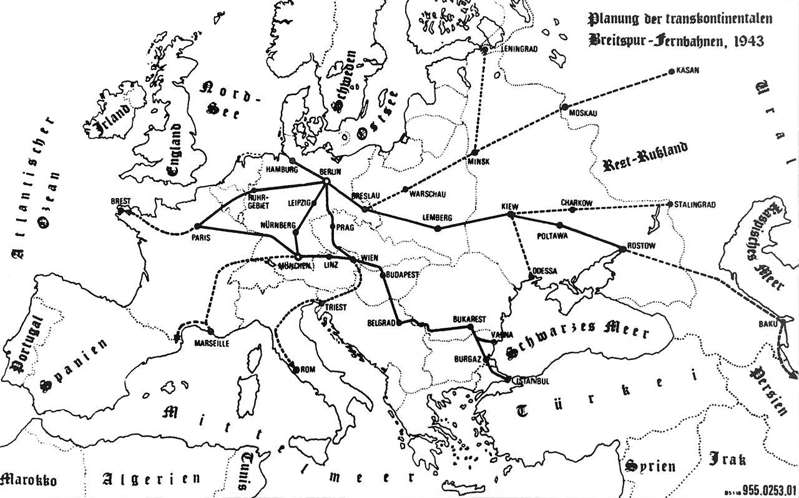

The first projects of railways, which could carry much more goods than conventional ones, and at higher speeds appeared in Germany in the late 1930s: the country was experiencing economic growth and preparations for war, and, consequently, increased trade and the load on the transport system has also increased. By the beginning of the next decade, especially after the advance of German troops to the east and in view of the need to implement plans to expand the living space of the German nation, the problem became especially acute.

The answer to this was the project of a broad-gauge railway with a distance between the rails of three meters, which is about twice as wide as the standard European (1.435 mm) and Russian (1.520 mm) gauge. The Minister of Armaments and Ammunition Fritz Todt proposed such a solution, and Adolf Hitler liked it very much, who ordered the construction of new highways and the development of trains for them as soon as possible. The Fuhrer's plans were grandiose: at least four pan-European routes ( Rostov-on-Don – Paris, Istanbul – Hamburg, Berlin – Rome and Munich – Madrid; see the image above) , four dozen variants of locomotives capable of accelerating a train up to 500 meters long, consisting of wagons over 40 meters long, 6–8 meters wide and over 7 meters high up to a speed of 200–250 km / h. Each such train could carry, as planned, up to 4,000 passengers and / or thousands (or even tens of thousands) tons of cargo.

By the end of 1942, the first experimental section of such a track was built in Germany, and although at about the same time Germany became a little bit out of touch with the grandiose railway, work on its creation was carried out until the fall of the regime that gave rise to it: German engineers systematically solved a lot of technical problems, connected with the creation of giant cars and locomotives – they invented the power supply, the signaling system, braking, overcoming air resistance, and so on. The main bottleneck of the broad-gauge railway – the economic efficiency of such highways – was not discussed: the project was personally dear to Hitler. In the end, nothing remained of the Breitspurbahn project, not even photographs.

Maglev

(Transrapid)

Nevertheless, Germany has been and remains one of the pioneers in the development of unique modes of transport. One such project is Transrapid : a high-speed magnetic levitation monorail, or maglev. The idea is simple and based on mutual repulsion of the same magnetic poles and attraction of opposite ones: some magnets are located on the track under the train, while others are located under the bottom of the cars. When current is applied, the train rises above the tracks to a height of 15 centimeters and can move at the same time. In this way, several inherent problems of railway and indeed any land transport are solved at once: there is no friction on the track and mechanical wear of parts, and the speed increases to 500 km / h.

The development of the Transrapid project began in 1969 by the efforts of engineers from the largest industrial concerns in Germany – Siemens and ThyssenKrupp . The test track and wagons were built by 1984 and testing of the system began. Around the same time, similar projects appeared in Great Britain and the USSR, and in Berlin at one time there was even a 1.5-kilometer M- ban branch, which, however, worked only on weekends and only for three years. It was not possible to agree on the construction of the commercial Transrapid line until 2004, when it was decided to build a 30-kilometer line in China – between Pudong Airport and Shanghai.

This project makes it clear why the Shanghai Maglev, built using Transrapid technologies, remains the only commercial line of its kind in the world: the cost of construction was at least $ 1.2 billion, and this does not include the money that has been invested since 1969 in system development and testing. In addition to the high cost, one should also note the impossibility of using the tracks of such a train for any other purposes, as well as the possible harm to human health and the environment, which is caused by a strong magnetic field created to levitate the train. That is why none of the projects in Germany have been implemented. Even worse, the test track Transrapid in Emland, Saxony, where the trials were conducted, was abandoned in 2012. The Shanghai magnetic levitation express continues to operate, to the delight of tourists and locals, and delivers passengers from the airport to the city in about 8 minutes at a speed of up to 430 km / h. But he is the only one in the world.

Photo and video: Wikimedia Commons, exsonvaldes / YouTube

Related materials:

- With the wind! 10 most unusual types of transport

- Traffic rules for chariots: the history of wheeled transport

- 10 grandiose transport facilities