Finland, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia withdraw from the Ottawa Convention and prepare to deploy millions of anti-personnel mines.

From northern Finland to eastern Poland, Europe is preparing to establish a new explosive line of defense – a kind of iron curtain mined with millions of devices.

The Telegraph writes about this.

All NATO countries bordering Russia or Belarus are coming to the conclusion that in order to contain a possible offensive, they need means that were recently considered unacceptable. If such a need arises, they will sow deadly traps among forests and lakes along the borders – anti-personnel mines, which at one time they tried to completely ban at the global level.

Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland have already announced their intention to withdraw from the 1997 Ottawa Convention, which bans the use of such mines. The countries are expected to formally notify the UN of their withdrawal in June, after which they will be able to produce, store and deploy the mines from the end of the year. Together, the five countries are responsible for protecting 2,150 miles of NATO's border with Russia and its ally Belarus.

Military experts are already planning which areas of the border will be mined if Russia decides to attack the alliance. These new plans mark the end of an era in which the world tried to eliminate the practice of using anti-personnel mines. With the start of Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022, international principles have changed. The ban, which seemed fair in peacetime, no longer holds up under the pressure of reality.

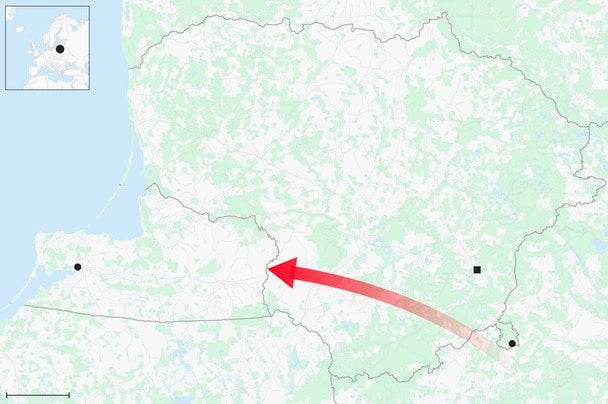

Among the countries returning to this practice, Lithuania is in a particularly difficult situation. It has two long hostile borders, with Belarus and Russia’s Kaliningrad region. Between these stretches is a key strategic area known as the Suwalki Gap, the only land route for reinforcing the Baltic states in the event of an attack.

Particularly vulnerable is the area where the Lithuanian bulge is, where the border with Belarus spans three sides and the distance to enemy territory is only a few miles. An example of this is the village of Šadžiūnai, where wooden houses are located on the very edge of the bulge. The surrounding area is covered in forests with deer and wolves, and the trails are marked with border guard warning signs saying “STOP” and requiring permission to enter.

Once past the official checkpoint, you are confronted by a view of a silver fence, reinforced with a coil of barbed wire, cutting through dense forest. This is not just the border between Lithuania and Belarus – it is the frontier of NATO, the edge of the outer West. And it is here that new minefields are likely to appear, making the already stern warning signs even more alarming.

Jadviga Mackiewicz, who lives in one of Šadžiūnai’s modest houses, was born here in 1941, the same year that Hitler invaded the USSR. Her most vivid memory is of 1944, when retreating Germans burned Šadžiūnai. “I cried so much: my village was on fire,” says 84-year-old Mackiewicz. “That’s the only thing I remember – that I cried.”

Today, the thought of another war fills her with fear and fatalism. “If God wills, perhaps it will pass. But war is war. It is better that it never happens again. I am very afraid. We are no longer young, we will soon go. But our grandchildren must live.”

Matskevich has three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, aged five and eight. All of her descendants have already left these lands. Only 13 people, all elderly, now live in the village of Shadžiūnai. Their homes are located a few meters from one of the most tense borders in Europe.

Matskevich doesn’t like the idea of planting mines on her own doorstep. “I wouldn’t be happy with that idea,” she says. “Animals might step on them and explode. I don’t have the strength to go into the forest anymore. I only go for firewood sometimes. But I can’t change anything. Let it be as it is.”

Many Lithuanian families are already preparing for war, spurred on by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In the village of Didei Baušiai, a mile from the border, Jurati Penkovskienė, 37, and her husband Vladislav, 41, have dug a bunker in their yard. In the basement are emergency supplies: 15 liters of water, a first aid kit, three shelves of canned goods. They are most worried about their baby, who is just six months old.

“Why did the Russians attack Ukraine? Because they want more territory,” Penkovskiene says. “So they might want ours, too.”

She is sure that NATO is the best guarantee of security. “There is a big difference between fighting alone and fighting with allies.” However, she has doubts about mines: “Perhaps they are needed for protection. But for people, it is bad. Mines will remain. And now we can freely go into the forest. After this, it will be psychologically difficult.”

The Lithuanian government acknowledges the seriousness of its decision to return to the production of anti-personnel mines for the first time in 22 years after joining the Ottawa Convention, which was supported by all EU countries.

She points to Russia’s illegal war against Ukraine, violations of international law, and provocations on the borders with Belarus and Russia as a direct existential threat. Shakalienė notes: Russia never signed the Ottawa Convention and continued to actively produce more mines than any other country, amassing more than 26 million by 2024. These mines maim and kill Ukrainians every day.

“Russia is not a party to the Convention and continues to use mines aggressively, putting us at a strategic disadvantage,” the minister concludes. “In such a situation, our armed forces need the freedom to use all possible means to protect people and NATO's eastern flank.”

Lithuania plans to spend 5.5% of its GDP on defence – more than double the UK’s current level of 2.3%. The country has already earmarked €800 million (around £680 million) for the production of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines.

Defence Minister Dovilė Šakalienė points to the real threat from Russia. “The attacks are already ongoing,” she says. “If you look at the map of all hybrid attacks – from cyberattacks and border provocations to continuous information campaigns – it becomes clear that the level of hostility from Russia towards Lithuania and the region is unprecedented.”

Šakalėne suggests that a Russian attack on NATO territory is possible in the coming years. “Both NATO and our military intelligence have repeatedly noted since last year: Russia may be ready to invade NATO territory in a period of three to five years – approximately between 2028 and 2030,” she says.

At the same time, this forecast could change. If the Ukraine talks end inconclusively, and Russia uses any ceasefire to rearm and bolster its military-industrial complex, perhaps with sanctions lifted, then the window of potential threat could shrink to two to three years.

For Šakalienė, like many Lithuanians, the restoration of Russia’s imperial ambitions is a personal matter. Her mother was born in Siberia, where her family was exiled during the Soviet occupation. Lithuania spent much of the 20th century under Nazi and Soviet rule. Even in January 1991, with the USSR on the brink of collapse, Gorbachev tried to stifle the country’s desire for freedom by sending tanks into Vilnius. Fourteen civilians died.

“Russia’s policy towards its Baltic neighbours is blatant imperialism and aggression,” Šakalienė says. “History has shown that Russia does not adhere to any agreements and respects only force. For Lithuania and the region as a whole, the only effective solution is full defensive readiness, unity of allies and reliable deterrence.”

Remembering its own history and the dangers that loss of independence brings, Lithuanian society and authorities are determined not to allow occupation again. Realizing the scale of the danger, the parliament decided in May to withdraw from the Ottawa Convention: 107 votes in favor, none against, three abstained.

Former Defense Minister Laurynas Kaščiūnas, who last year initiated a plan to use anti-personnel mines to deter aggression, notes that the weapons are a key element of Lithuania's “countermobility” strategy, which is designed to make it more difficult for enemy forces to advance.

“Mines – anti-tank, anti-personnel, anti-vehicle – work together to create a serious obstacle for the enemy,” he notes. “They need time to break through these lines, and this gives the opportunity to hit them from a distance, hold up their advance and buy time for regrouping and reinforcing allies.”

Kasciunas also explains that mines are just one element of a broader defense system. It will include physical barriers against tanks, like dragon teeth, attack drones, and long-range weapons.

Kasciunas’s visits to Ukraine after the outbreak of full-scale war finally convinced him that the time for good intentions was over. “The Ukrainians told me clearly: while you have time, withdraw from all conventions and prepare to use everything possible to defend the country,” he recalls.