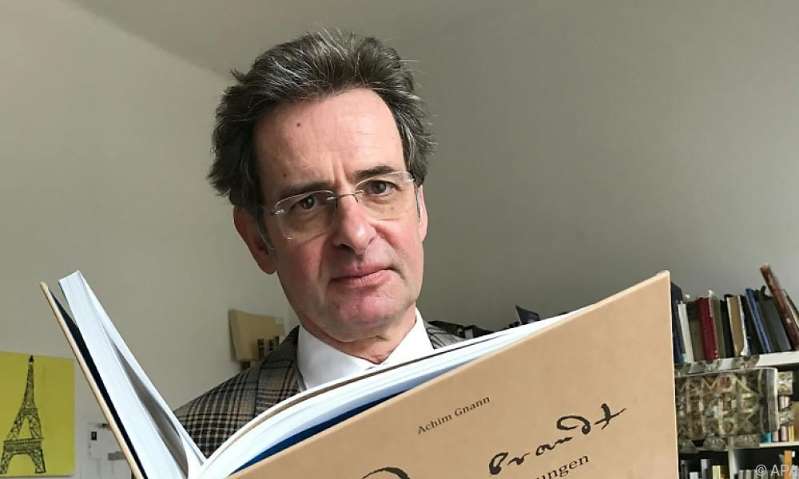

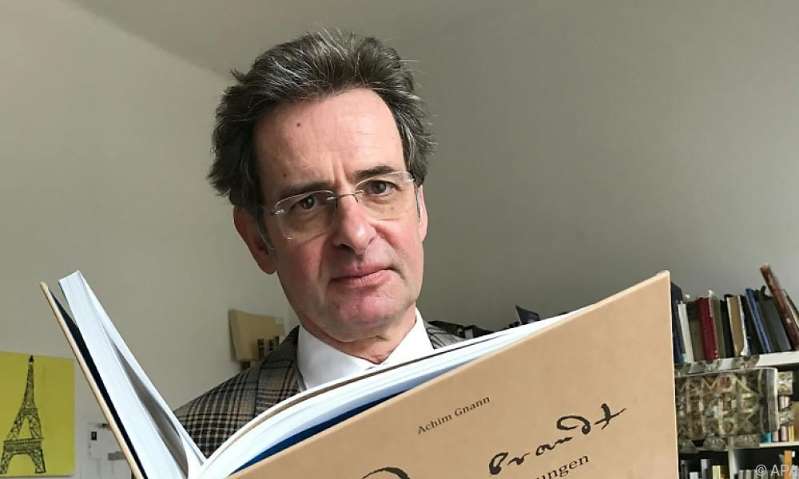

“Rembrandt. Landscape Drawings” is the name of the book in all its simplicity. Its author, Albertina curator Achim Gnann, is leafing through the freshly printed work that is being delivered these days with some pride. And says, “I think this is going to be a lot of trouble.” As the? Does he, too, as has long been customary in the industry, doubt that many works were drawn by the master himself? No, the exact opposite is the case.

Image: APA

Gnann works in his book, which he completed in the Corona short-time work of the first lockdown, as a kind of revisionist. He revised most of the numerous write-offs of the past decades, when it became clear that many drawings were made by Rembrandt's students or epigones. Through precise chronological assignments and detailed analyzes, he believes that he can prove that it is indeed Rembrandt's own work. “I hope that my work will inspire the Rembrandt picture to be reconsidered. I hope for a strong response. But I will probably get a lot of beatings because I have dealt with Rembrandt for a long time, but have never published about him have.” Rather, Gnann is a specialist in Italian art, has habilitated on the more than 1,000 sheets of drawing by Parmigianino and has curated sensational exhibitions on Raphael and Michelangelo at the Albertina, where he has been employed since 2005.

In his book, Gnann focuses on the landscape drawings that Rembrandt created from around the mid-1630s to the mid-1650s. The approximately 260 leaves that have been preserved “breathe the freshness and immediacy of the impression of nature that the artist was able to bring to paper on his forays through the area around Amsterdam and other places,” enthuses the art historian in his foreword. “Rembrandt practically absorbed nature in himself, whereby for him it is not about the large and representative, but about the simple, intimate and special that make a view unmistakable.”

Today's Rembrandt research has recently only accepted around 100 of these sheets as Rembrandt originals. What makes Gnann so certain that the drawings he “returned” to Rembrandt really come from his own hand? On the one hand, there are meticulous comparisons with studies, etchings and paintings at the same time that have made it possible for the first time to date most of the drawings almost exactly. “That is very difficult, because there is little evidence for Rembrandt,” says Gnann, “but with the correct chronological classification, the picture also fits together correctly.” On the other hand, the overall effect of Rembrandt's drawings is unique: “He had an unbelievable eye for details, light and atmosphere and what these things trigger in the viewer. In this way he creates real landscape experiences. Each subject gets its own conciseness. His students have not that depth, “he is sure. “I think it's a mistake to fixate too much on the detail as it obscures the overall picture that really matters.”

A side effect of the new publication is that some drawings from the Albertina's holdings are attributed to Rembrandt again in this way. There is also another reference to the Albertina: The six-volume catalog raisonné of Rembrandt drawings published by the former Albertina director Otto Benesch (1896-1964) in the 1950s was considered a standard work for a long time before the “complete clear-cut” of research began who radically reduced the number of originals. With him, “almost everything is inside again,” says Gnann. “In principle it is a Benesch rehabilitation.”

(SERVICE – Achim Gnann: “Rembrandt. Landscape Drawings”, English / German, Imhof Verlag, 368 pages, 81.20 euros)