Scientists believe that severe flooding and subsequent low tides in the Congo Basin led to a powerful avalanche

Scientists report the most powerful underwater avalanche ever observed by oceanographers. It happened in an underwater canyon that originates from the mouth of the Congo River off the coast of West Africa.

The phenomenon was recorded back in January last year, but it took the scientists time to repair the equipment broken by a powerful avalanche and process the data. Together with the inventory of oceanographers, the underwater communications system was damaged, which is responsible for the transfer of 99% of all data in the world.

More than one cubic kilometer of sand and mud descended to the depth of the canyon. The natural phenomenon lasted two days and covered an area exceeding 1.1 thousand kilometers of the Atlantic Ocean floor.

- Where does the internet come from? Google and Facebook pull cables across the oceans

- Can Russian submarines leave the world without internet?

- Google lays its own submarine cable to Europe

There are many underwater canyons at the bottom of the oceans. The depression, originating at the mouth of the Congo River, where the descent took place, is one of the largest in the world.

Usually this is a V-shaped depression, the depth of which is a thousand or more meters relative to the bottom.

Repair vessel The Leon Thevenin was sent to the coast of West Africa to repair submarine cable breaks caused by a submarine avalanche in 2020

This phenomenon would not have come to the attention of scientists if the moving sand had not cut off two undersea communication cables, which disrupted the Internet throughout the territory between Nigeria and South Africa.

Special devices, laid along the entire length of the canyon, help to measure the speed of movement of sediments and their mass.

“Several of our oceanographic stations were damaged, they were literally ripped off the anchors with which they are attached to the bottom. From them we received an e-mail about what was happening,” says Peter Tolling, professor at Durham University.

“The movement of the avalanche grew and grew. It lifts sand and mud from the bottom, which makes the flow denser and faster,” the scientist explains.

With the help of such devices, scientists can observe underwater phenomena and assess the associated risks to human life.

According to scientists, the movement of the most powerful stream was provoked by two factors.

The first is an exceptionally severe flood in the Congo River in December 2019, about two weeks before the start of the movement of the underwater mass. Such floods occur about once every 50 years and bring large amounts of sand and mud to the river mouth.

Then, unusually strong ebb and flow began in January.

“We think the mass started in shallow water, at low tide,” says Professor Dan Parsons of the University of Hull. “As the pressure on the ocean in the upper layers decreases, the pressure in the bottom sediments changes, which leads to such consequences “.

Analysis of data from measuring instruments shows that the avalanche made its way from shallow water to a mark of 4500 meters in one piece.

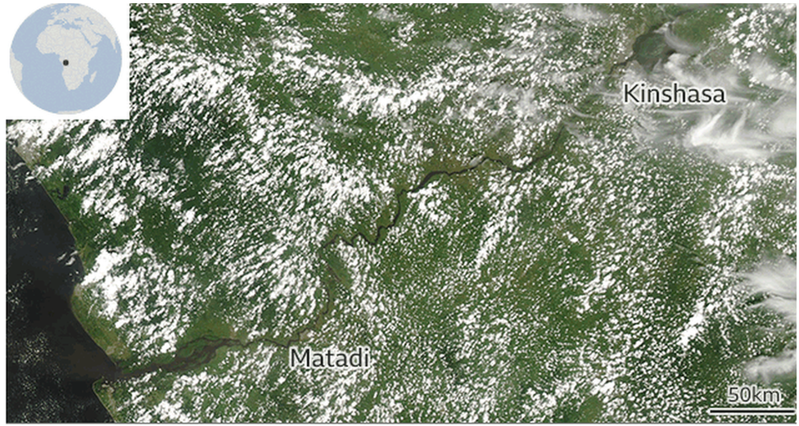

During the 2019 flood, water in the Congo Basin arrived at a speed of 70 thousand cubic meters per second. Source: NASA WorldView

Scientists were able to determine the scale of the phenomenon only after repairing the sensors, guided only by approximate data on its initial phase.

It is known that in the upper reaches of the canyon the stream moved at a speed of 5.2 m / s, and by the end of its path it accelerated to 8 m / s.

It took about three weeks to fix cables damaged in January last year.

There is one interesting observation that perhaps explains why some cables break and others do not.

This is due to the fact that the avalanche interacts with the bottom surface in different ways at different parts of its path: somewhere it completely destroys its layers, somewhere it slips, leaving behind an extra layer of sand.

In the waters of the oceans, repair vessels are constantly plying, ready to quickly eliminate breakdowns in the system of underwater communications, which has become vital

“This new data will be used by the communications industry to create new routes along the ocean floor, bypassing areas with the greatest risk of erosion, harmful to technology,” says Mike Clare, a marine geologist at Britain's National Oceanographic Center.

The importance of underwater communications systems, through which 99% of intercontinental data exchange is carried out, cannot be overestimated. For example, remittances alone around the world are worth trillions of dollars a day.

Research in the Congo Basin is becoming one of the priority international projects, which has been joined by scientists from France, Germany and Angola.